Collage art and activism in Chile: Instagram posts building on the legacy of Latin American ‘mail art’

Collage art and activism in Chile: Instagram posts building on the legacy of Latin American ‘mail art’

Sebastian Bustamante-Brauning, University of BristolSince widespread protests started in October 2019 in Chile, social media has become a key way for artists and activists to circulate and exchange information and ideas. Independently curated Instagram feed @CollageChile has taken a particularly prominent role. The work, in form and dissemination, echoes 20th-century mail art and collage practice from Latin America, a practice that involved postcard-sized art sent through the postal system that challenged the region’s authoritarian regimes in the 1960s and 80s.

On October 18 2019, protesters took to the streets of the Chilean capital Santiago, angered by a proposed increase in Metro fares. What started as a local protest about a specific issue, led to rioting and exposed mass discontent. The protests are the largest the country has seen since the end of the military dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet in 1990.

Chile’s president Sebastian Piñera, who is politically centre-right, responded by putting the military on the streets and declaring a state of emergency. He declared: “We are at war against a powerful enemy, who is willing to use violence without any limits”.

Piñera’s actions produced further protests and he was forced to table constitutional change. The president’s comments – and the ease with which he imposed severe measures – prompted widespread disapproval by Chileans who took to social media with the hashtag #noestamosenguerra (#wearenotatwar).

Instagram activism

Activists have used social media to report and denounce human rights abuses by police and military. Videos posted show police beating and firing live rounds at unarmed protesters. Particularly gruesome images show the results of police firing pellets directly into protestors’ faces to blind them.

Artists on @collagechile have also used its large and instantaneous networks for political effect. A feed of images from the past connect viewers with what is at stake in the present.

Perfecto distingo lo negro del blanco (Perfectly I Distinguish Black from White) by @mattialmg takes its title from Chile’s foremost poet and songwriter, Violeta Parra. Parra’s folk protest songs still resonate in Chile after her death in 1967. Parra is depicted wearing an eye patch, a symbol for protesters blinded by police. The collage implies that while the state blinds its citizens to reality, both literally and metaphorically, people cannot be prevented from seeing realities of inequality and state violence in Chile today.

Pinochet’s face menaces some of the collages, highlighting that the current government’s reaction is a dark reminder of his dictatorship from 1973 to 1990. In fact, Piñera relied on powers rooted in the constitution drafted and implemented by Pinochet’s regime (Articles 39-45) and commentators question whether they have been used legitimately in this case. Many have fought for greater changes to Pinochet’s constitutional legacy, which they believe favours the country’s political and economic elite.

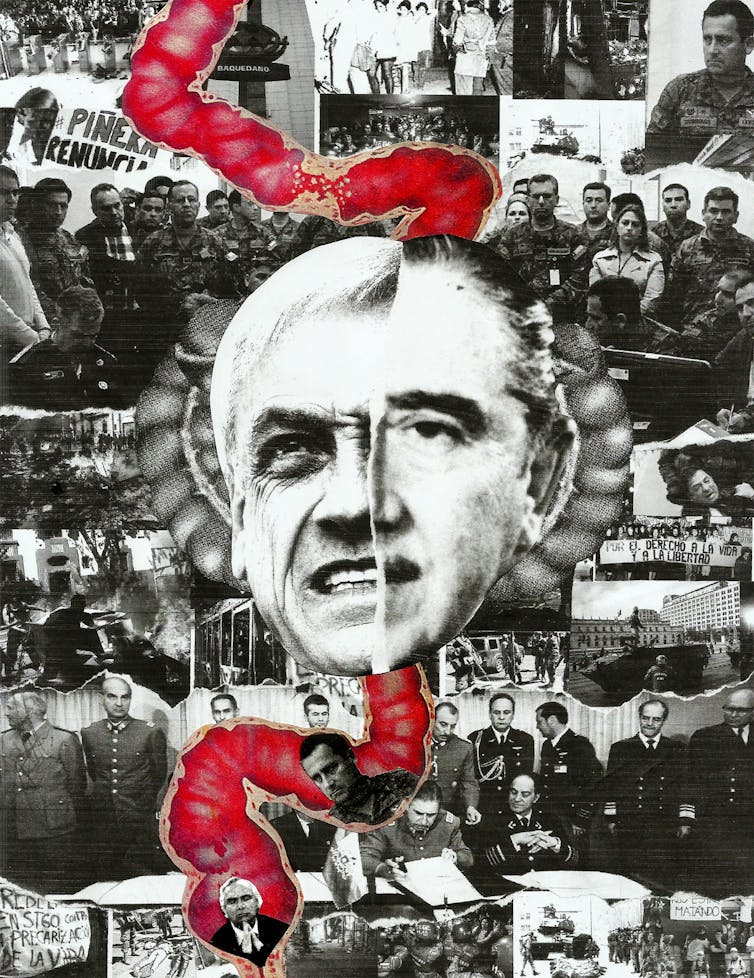

In La misma mierda, distinto olor (Same shit, different smell) by @ordeph, images of Pinochet’s military junta are mixed with images of contemporary politicians. Piñera’s face is positioned next to Pinochet’s, their faces connected by a bold red intestinal shape. Chile’s past is digested and blended with the present to link the past’s authoritarian leaders with today’s politicians.

La misma mierda, distinto olor!!

@Ordep/Instagram, Author provided

Sharing these image via social media builds on a legacy of artists using collage and disrupting media messages seen in Latin American mail art, which began to be practised in the 1960s and was a global movement. Mail artists created small postcard-sized art works which included visual poems, collage or drawings that were shared through the postal system.

Social media, however, takes these exchanges further by connecting more people via hashtags and Instagram feeds. Each time Piñera restates that the country is in a war with a powerful enemy, artists respond quickly with collages that challenge the president’s own narrative.

Pre-digital circuits of exchange

Artists in South America engaged with the practice to subvert censorship and create circuits of exchange to challenge dictatorships. The Chilean artist and poet Guillermo Deisler highlighted abuses committed by Pinochet’s regime in his mail art. First imprisoned following the coup, Deisler sent postcard-sized artworks such as Aktion por Chile y America Latina in 1985 from his exile in East Germany.

Brazilian artist Cildo Meireles’s Insertions into Ideological Circuits in the 1970s involved stamping banknotes with demands for answers regarding political killings by the state. He also used recycled Coca Cola bottles to insert subversive messages into public circulation.

Forced to flee to Brazil in 1976 after political persecution, Argentine artist León Ferrari collected newspaper clippings related to disappearances, detentions and the discovery of mutilated bodies during the last Argentine dictatorship (1976-1983). Ferrari received more in the mail and compiled these into Nosotros no sabíamos (We Didn’t Know, 1976) – a folio challenging Argentine society’s silence on the dictatorship’s brutality.

It was dangerous to make and receive mail art in Latin America. Like many others, Clemente Padín in Uruguay was imprisonedin 1977 and Argentinian mail artist Edgardo A. Vigo’s son was “disappeared” during the dictatorship.

Deisler, Meireles, Ferrari, Padín, Vigo and others faced down these risks to use existing communication systems to denounce injustice, subvert censorship and traditional circuits of exchange. This legacy of art which challenged dominant political slogans is used by collage artists in Chile today.

In the digital era, the internet has become the primary means to challenge mainstream media. While undeniably it is used to share information of dubious origin, social media is a powerful information exchange circuit. Online media reach audiences unthinkable in the age of broadcast and postal circulation.

By reminding viewers of the recent past and documenting current injustices, the images shared through platforms such as Collage Chile become the new digital insertions into ideological circuits. And, in this they are continuing a legacy of socially engaged art practices in Latin America.

Current collage art, as shown on Collage Chile’s platform, builds on a tradition of practice in Latin America that challenges abuses of power and social inequality. From the generation of artists who were killed and had to leave their countries due to dictatorships, a new generation has emerged who insist that the past’s abuses should never be repeated. This generation have the ability to share their work globally through social media and form new online communities of resistance.![]()

Sebastian Bustamante-Brauning, Doctor of Philosophy Student, University of Bristol

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.